When I was little, my godfather spoke often about a Meissen porcelain platter that he'd hidden in his knapsack during the last days of World War II. He'd guarded it fiercely, refusing to let it out of his sight until he could bring it home as a trophy of the war. He assured us that it had belonged to Hitler, and had been part of the Führer's own dinner service.

To be honest, I don't remember the actual platter itself. Had my godfather sold it? Did it failed to survive the Atlantic crossing back to New York? I don't know. But even then it was clear to me that the real significance of the platter to my godfather wasn't its intrinsic value, but that it represented a piece of the enemy that he'd won and kept, a trophy to be proudly discussed and marveled over for the rest of his life. It was tangible proof that when he'd fought for his country, he'd been among the victors.

Of course, my godfather wasn't alone in this. No matter how much officers frown and governments try to outlaw looting, soldiers have always brought home "souvenirs" from their battles and their enemies - the infamous spoils of war.

I thought of that when I first saw these baby shoes, right, cut from the red wool of a captured British uniform coat, and on display at the Museum of the American Revolution. The shoes belonged to the children of Sgt. James Davenport of Massachusetts, and were fashioned from the captured coat of a British soldier during the Revolution. To Davenport, who lost two brothers in the war, the shoes must have been a poignant reminder of the cost of liberty won for the next generation.

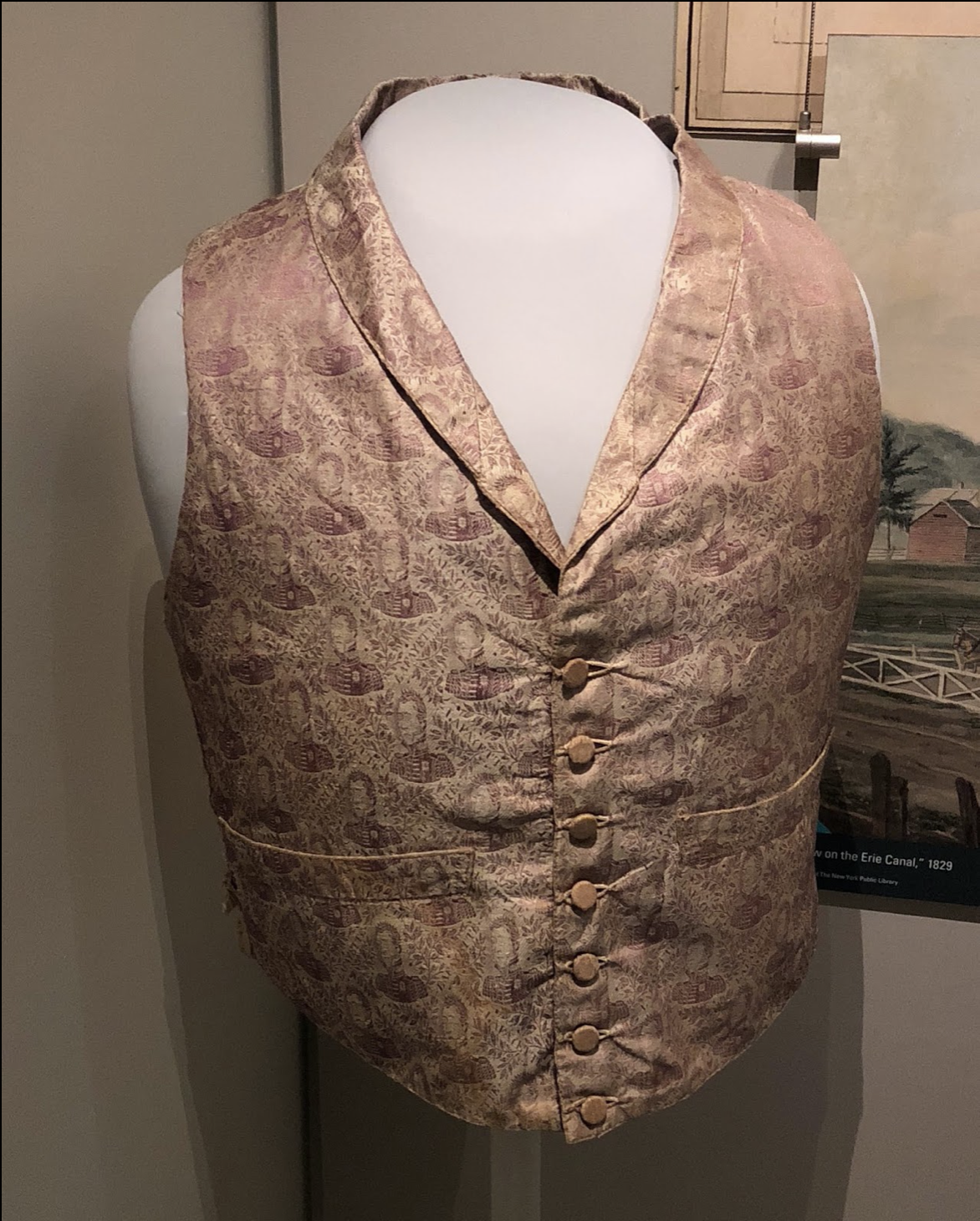

I thought of it again, too, when I saw the quilt, above, on display at Winterthur Museum. Although the quilt is believed to have been made in the early 19thc, a family heirloom from the American Revolution dominates the patchwork pattern. The unusual scarlet shape in the middle is a man's 18thc red wool cloak. The larger semi-circle would have wrapped around the wearer's shoulders, while the smaller semi-circle would have folded back around the neck into a collar. The cloak would have been worn over another coat as an extra layer of warmth and protection during a harsh winter.

Family tradition says the cloak was captured from a British soldier by an ancestor fighting in the northern campaigns, where the weather was coldest, during the American Revolution. The cloak was then likely passed down through the next two generations, and probably with a tale or two attached as well. Winterthur believes the quilt was most likely made by Myranda Codner Patterson (1808-1881) around the time of her marriage to Thomas Patterson in 1828. From there, the trail becomes a bit more hazy. There were several ancestors in the Codner and Patterson families who were the right age to have fought with the Continental Army, but it's unclear which one might have actually captured the cloak.

No matter. When Myranda (or whoever else might have made the quilt) began to cut her patchwork pieces, she left the bright red wool cloak untouched, and instead incorporated its geometric shape into her design. It's easy to imagine the stories that surrounded the quilt after that. Imagine being a child tucked beneath it, and hearing about how your brave ancestor plucked this very cloak from the shoulders of a wicked redcoat officer. Imagine touching that red wool as you drifted off to sleep, and dreaming of hard-fought victories won for the sake of liberty and America.

Much like my godfather and that Meissen platter.

Above: Quilt with inset 18thc men's cloak. Possibly made by Myranda Codner Patterson, possibly Ohio, early 1800s. Winterthur Museum. Photo courtesy of Winterthur Museum.

Right: Child’s Shoes, 18thc., maker unknown, Museum of the American Revolution.

My latest historical novel, The Secret Wife of Aaron Burr, is now available everywhere. Order here.