The Battle of Yorktown has been a popular topic on social media this past week after the television series TURN: Washington's Spies featured the siege in last Saturday's episode, and an excitingly smoke-and-explosion filled depiction it was, too.

Yorktown was Alexander Hamilton's last moment to shine on the revolutionary battlefield, and he knew it. Although he had fought bravely and efficiently in battle during the early days of the war, he had spent most of the conflict at a desk as one of General George Washington's aides-de-camp. It didn't matter that he had in fact become the general's "right hand man", briskly handling not only Washington's correspondence, orders, and the headquarters' finances, but also serving as an interpreter during delicate negotiations with French allies. Alexander felt he was no better than a secretary, and longed for the opportunities of battle. He was right, too. No one would remember his skillfully written letters on behalf of his general. Military glory and fame would last beyond the war, and with his lack of a fortune or famous family, such a reputation would be necessary to carry him to the next stage of his life.

For years Washington had resisted Alexander's pleas for a field command, until the summer of 1781, when at last Alexander was made commander of a battalion of light infantry. Alexander was elated. This was exactly what he'd most desired: the light infantry were the Continental Army’s elite assault troops. It was clear that a major, and perhaps final, battle was coming that would likely decide the war, and now he was sure to be in the thick of it.

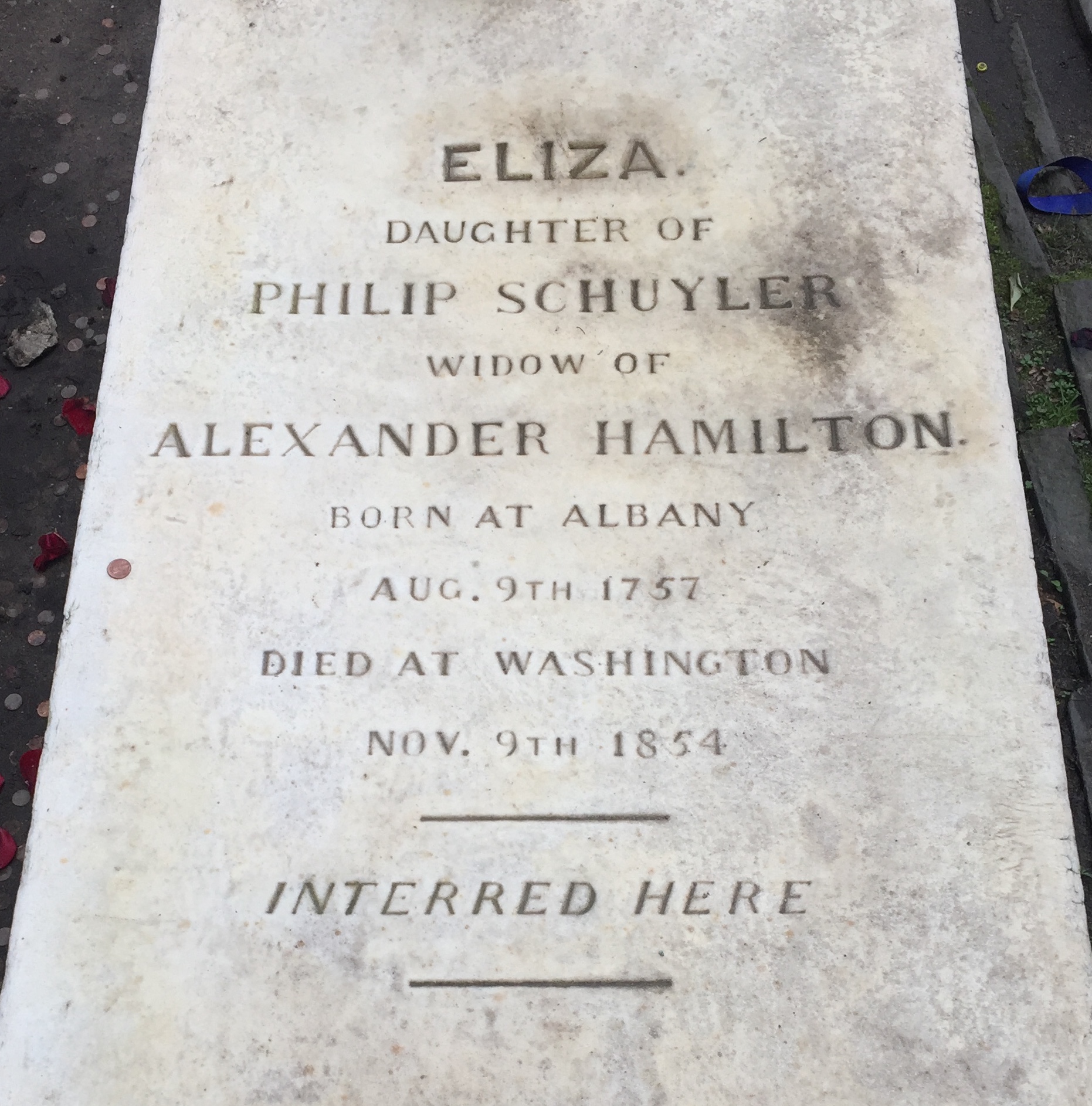

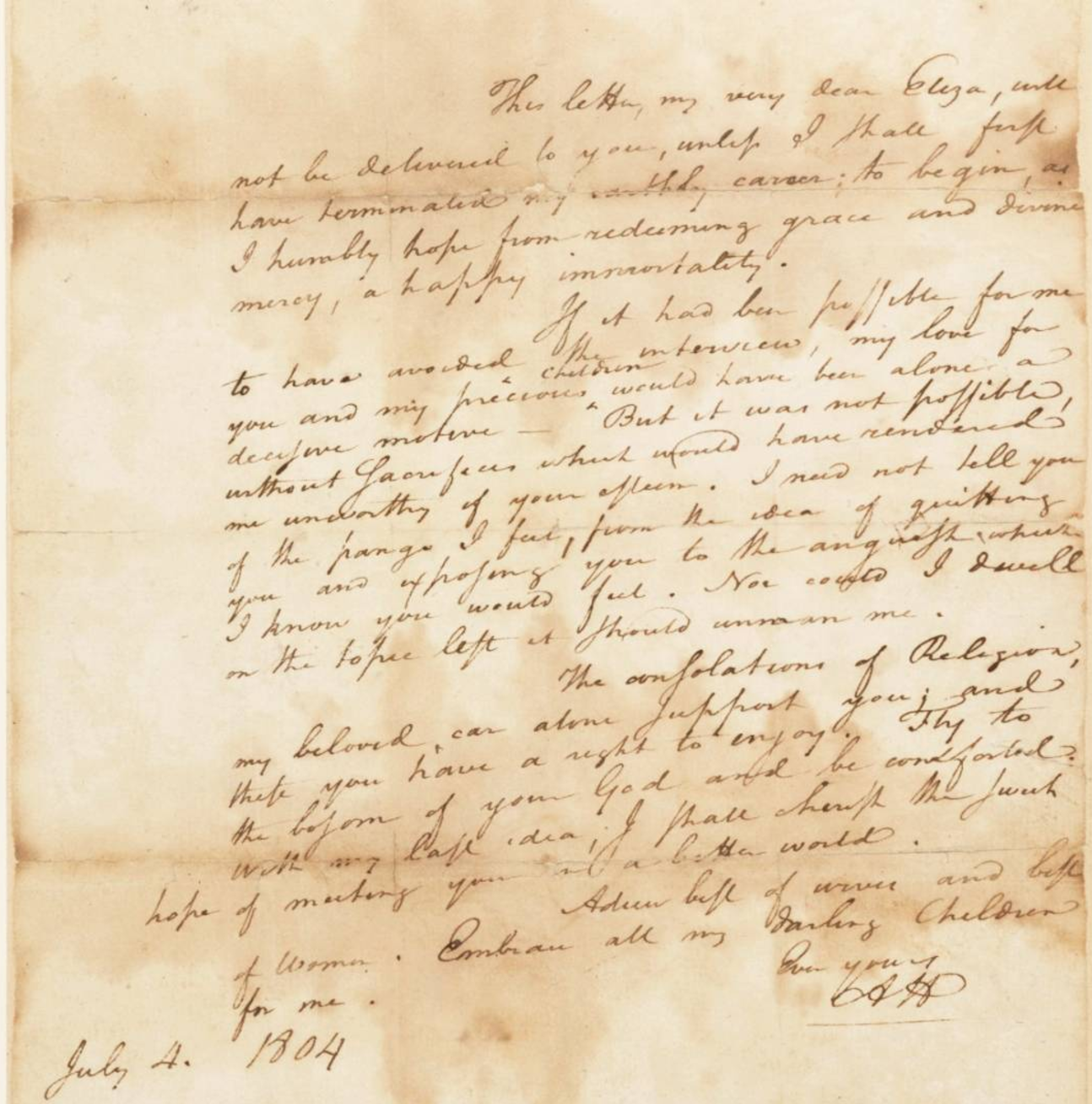

And yet pulling at his heart throughout all this was Eliza. They'd been married less than a year, and she was expecting their first child in January. Although she was safe with her parents at The Pastures in Albany, she was still never far from Alexander's thoughts throughout the late summer as the army marched south towards Virginia. Given the circumstances, it's likely that many of their letters arrived out of sequence, or perhaps not at all. The tone of his letters to her bounces back and forth: in one eager sentence his anticipation is palpable as he tells her more than he should about the army's movements, and in the next he wants her to know how deeply he loves her in case he doesn't return.

In September, he wrote to her from Elkton, MD:

"To-morrow we embark for Yorktown.... I would give the world to be able to tell you all I feel and all I wish, but consult your own heart and you will know mine....Circumstances that have just come to my knowledge, assure me that our operations will be expeditious, as well as our success certain. Early in November, as I promised you, we shall certainly meet. Cheer yourself with this idea, and with the assurance of never more being separated... be it my object to be happy in a quiet retreat with my better angel." (You can read the entire letter here.)

A week later in Annapolis, MD, he had time to write only a few sentences, tinged with melancholy:

"How chequered is human life! How precarious is happiness! How easily do we often part with it for a shadow! These are the reflections that frequently intrude themselves upon me, with a painful application. I am going to do my duty. Our operations will be so conducted, as to economize the lives of men. Exert your fortitude and rely upon heaven."

On October 12, camped at Yorktown, VA, he longs to be with her and their unborn child:

"The idea of a smiling infant in [your] arms calls up all the father in it. In imagination I embrace the mother and embrace the child a thousand times. I can scarce refrain from shedding tears of joy. But I must not indulge these sensations; they are unfit for the boisterous scenes of war and whenever they intrude themselves make me but half a soldier. Thank heaven, our affairs seem to be approaching fast to a happy period... Five days more and the enemy must capitulate or abandon their present position; if they do the latter it will detain us ten days longer; and then I fly to you. Prepare to receive me in your bosom. Prepare to receive me decked in all your beauty, fondness and goodness. With reluctance I bid you adieu." (Read the whole letter here.)

Two nights later, Alexander was an important part of the planned attack. Under cover of darkness, smoke, and fog from the river, he led his troops towards a strategically important earthworks fortification known as Redoubt 10, manned by about 70 British and Hessian forces. To preserve the element of surprise, Alexander's men attacked with unloaded muskets, relying instead on only their bayonets. While the British fired upon them, Alexander charged up the palisades ahead of his men; he was the first to jump into the redoubt as other Continental troops swarmed the redoubt from the rear to end any hope of a British retreat. Thanks to daring and courage, the redoubt was captured, and victory soon followed for the combined Continental and French forces. And, finally, Alexander was lauded as a hero.

But his brief letter to Eliza two days later downplayed his heroics, and if anything, he seems almost sheepish in admitting the danger in which his bravery had placed him, and promising her he won't do it again:

"Two nights ago, my Eliza, my duty and my honor obliged me to take a step in which your happiness was too much risked. I commanded an attack upon one of the enemy’s redoubts; we carried it in an instant, and with little loss. You will see the particulars in the Philadelphia papers. There will be, certainly, nothing more of this kind; all the rest will be by approach; and if there should be another occasion, it will not fall to my turn to execute it."

Days later, Alexander was on his way again, racing back to Eliza in Albany. His battlefield role in the war was done, and his reputation as a hero secured. Soon he would be back safely in Eliza's arms in time to welcome their first child together in January, 1782.

The remnants of those same redoubts from the siege are still visible at the Yorktown Battlefield, above. Now they're protected by metal fencing instead of British artillery. They're thick with grass and weeds, and the land surrounding them is peaceful and green. But if you listen closely (and your imagination is like mine), you can still hear the sounds of battle, and victory.

Photograph copyright 2017 by Susan Holloway Scott.

Read more about Eliza Schuyler and Alexander Hamilton in my latest historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton, now available everywhere. Order now.