If you're reading this blog, you're most likely a history nerd as well as a Hamilton fan, and proud of it, too. It also likely means that somewhere you've recently read this history story in the mainstream media: how a few strands of George Washington's hair were discovered tucked inside a 200-year-old almanac in the rare book library of Union College. Partly because it was around Washington's birthday, and partly because it IS an interesting discovery, the story was everywhere, including the Washington Post, The New York Times, USAToday, Newsweek, Newsday, US News & World Report, and the Smithsonian's SmartNews, NPR, and network and cable outlets as well. Last time I checked, it had appeared in over 200 outlets.

In many versions of these stories, I'm quoted (along with professors of history and hair-experts), describing how hair was a common memento among friends and family in the past. Which, of course, it was - but there's much more to the story than most journalists have space to tell. I don't have those constraints, and besides, I love all the nerdy-history details. There are even connections to Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, the heroine of my historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton.

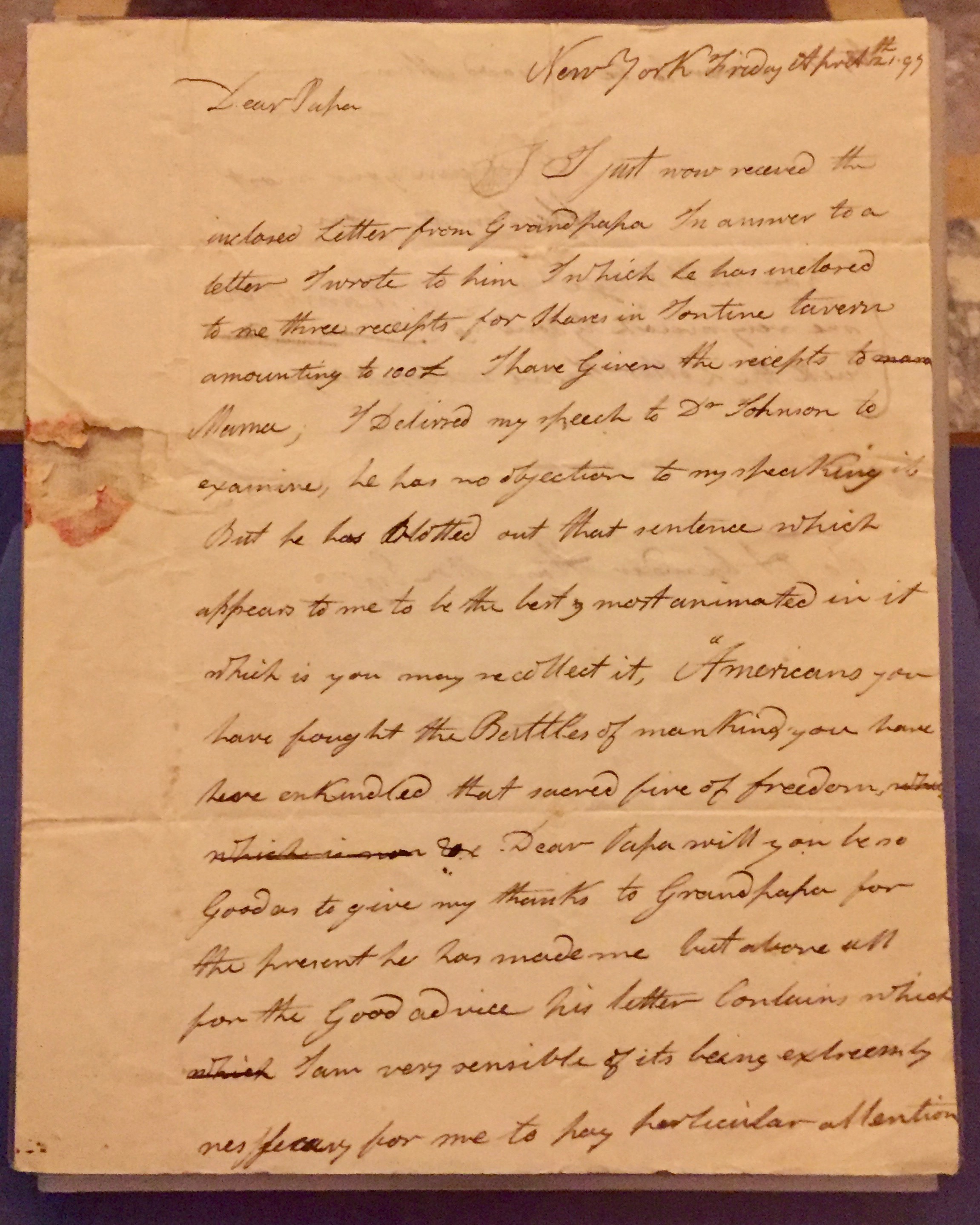

The almanac - and the hair - (shown above) were discovered during an inventory of the archival collections of Schaffer Library, Union College. Bound in red leather, Gaines Universal Register or American and British Kalendar for the year 1793 was a popular volume for gentlemen of the time, and contained useful, everyday knowledge such as population estimates for American cities and comparisons of various coins and monies. The almanac is inscribed "Philip Schuyler's a present from his friend Mr. Philip Ten Eycke New York April 20, 1793."

The first thought was that the almanac belonged to Gen. Philip Schuyler (1733-1804), a close friend of Gen. Washington who served under him during the American Revolution. Philip Schuyler was later active in Federalist politics and government as a U.S. senator from Albany, as well as one of the founders of Union College. He was also the father of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton (1757-1854), and father-in-law to Alexander Hamilton.

Tucked inside the almanac were several pages of handwritten notes and a business letter, which make the owner more likely General Schuyler's son, Philip Jeremiah Schuyler (1768-1835). Also inside the almanac was a slender yellowed envelope, with this written on one side: "Washington's hair, L.L.S. & (crossed out) GBS from James A. Hamilton given him by his mother, Aug.10, 1871." Inside the envelope were a few white hairs, tied together with a thread, left. Who were all these people, and could their identities help prove that the hair really had come from Washington?

A Google search by Phillip Wajda, Union's director of media and public relations brought him to my blog post about historic hair in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. The handwriting accompanying that hair does appear to the be same as is on the envelope, belonging to James Alexander Hamilton (1788-1878.) James was the fourth child of Elizabeth and Alexander Hamilton, and, like his mother, was very aware of both his father's legacy and his family's place in American history.

Locks and strands of hair were often exchanged, especially as tokens of a deceased loved one. While it's impossible to be absolutely certain without DNA testing, the hair's provenance makes a strong case for it having come from Washington. The Hamiltons were close to the Washingtons, and it's likely that Martha shared George's hair with Elizabeth after George's death, if not before. It therefore makes sense that James passed along the hair given to him by his mother, Eliza, as he wrote on the envelopeHe gave the hair to family members who would have appreciated it, too. Thanks to the assistance of Jessie Serfilippi, an interpreter at the Schuyler Mansion in Albany, we determined that the initials refer to James's granddaughters, Louisa Lee Schuyler (1837-1926) and Georgina Schuyler (1841-1924.) The sisters continued the family interest in history through historic preservation - an idea growing in the late 19thc-early 20thc with a renewed appreciation for the country's early history. Together the sisters were instrumental in making Gen. Schuyler's grand colonial house in Albany into a New York historic site in 1917. At some point, the envelope with the hair must have been slipped into the almanac for safekeeping, forgotten, and then later donated to Union.

A digression into the complicated genealogy of Louisa and Georgina: Philip Jeremiah Schuyler (son of Gen. Schuyler, brother of Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton, and owner of the almanac) and his second wife, Mary Anne Sawyer, had a son, George Lee Schuyler. George Lee Schuyler married his cousin Eliza Schuyler, the daughter of James Alexander Hamilton (son of Elizabeth and Alexander Hamilton.) George and Eliza became the parents of Louisa Lee and Georgia - who therefore were, through intermarriage, great-granddaughters to both Gen. Philip Schuyler and Alexander Hamilton. Whew!

What I find particularly fascinating about all this is that because Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton lived to be 97, she would have known both Louisa Lee and Georgina as girls. Think of that: they would have heard first-hand stories of the American Revolution from Elizabeth, and yet they themselves lived into the 1920s. It's understandable that Louisa Lee and Georgina would have wanted the Schuyler Mansion to be preserved since they remembered their great-grandmother, who in turn would have remembered when the mansion (then her family's new home, known as The Pastures) was built in the 1760s.

Could there be any better backstory than that?

Thanks to Phillip Wajda, Jessie Serfilippi, and Anne E. Bentley, Curator of Art & Artifacts, Massachusetts Historical Society, for their assistance with this post.

Photo ©2018 Union College.

Read more about Eliza Schuyler and Alexander Hamilton in my historical novel, I, Eliza Hamilton. My latest novel, The Secret Wife of Aaron Burr, is now available everywhere. Order here.