Like far too many 18thc women, Esther Edwards Burr (1732–1758) is today remembered mainly because of her father, her husband, and her son. Born along the New England frontier in Northampton, MA, Esther was one of eleven children. She was given an unusually good education for a girl of her time, and from her surviving letters it’s clear she was thoughtful, intelligent, observant, and articulate - all qualities she passed along to her son.

She was also deeply religious. Her father was Jonathan Edwards, regarded today as the most important and influential theologian and clergyman in 18thc America. Esther’s childhood coincided with the Great Awakening, a revival of spiritual fervor with her father and his teachings at its core. Esther often turned to scripture for solace and explanations, but she also seems to have had difficulty reconciling her beliefs with her more worldly thoughts.

She married Aaron Burr, Sr. (1716-1757) in 1752 when she was twenty. He was sixteen years older, a rising star in the evangelical Presbyterian church, and the second president of the still-new College of New Jersey (which would evolve into Princeton University.) They had first met when he had come to Connecticut to converse with her father; she had been only fourteen at the time, but apparently Burr was sufficiently impressed to return six years later to court her. That courtship lasted less than a week before Esther accepted his offer of marriage, and traveled with him back to New Jersey.

The marriage seems to have been a happy one. Esther, however, desperately missed her friends and close-knit family. Her new husband’s duties frequently kept him away from home, and Esther found her own responsibilities as the president’s wife - including what sounds like a constant stream of visiting colleagues and students in their home - exhausting. She made few friends in their social circle, finding most of the women not only much older, but dull and intellectually underwhelming.

After a lengthy visit from her oldest and dearest friend, Sarah Prince, who resided in Boston, the two began to keep journals to compensate for the physical distance between them. Taking the form of continuing letters, the friends intended to exchange the journals at a later date. Only Esther’s journal survives. Intended for Sarah (whom she addressed as “Fidelia”) alone, the letters are startlingly frank, succinctly describing people, places, and events, and sharing both Esther’s dreams and fears as well as the details of her everyday life.

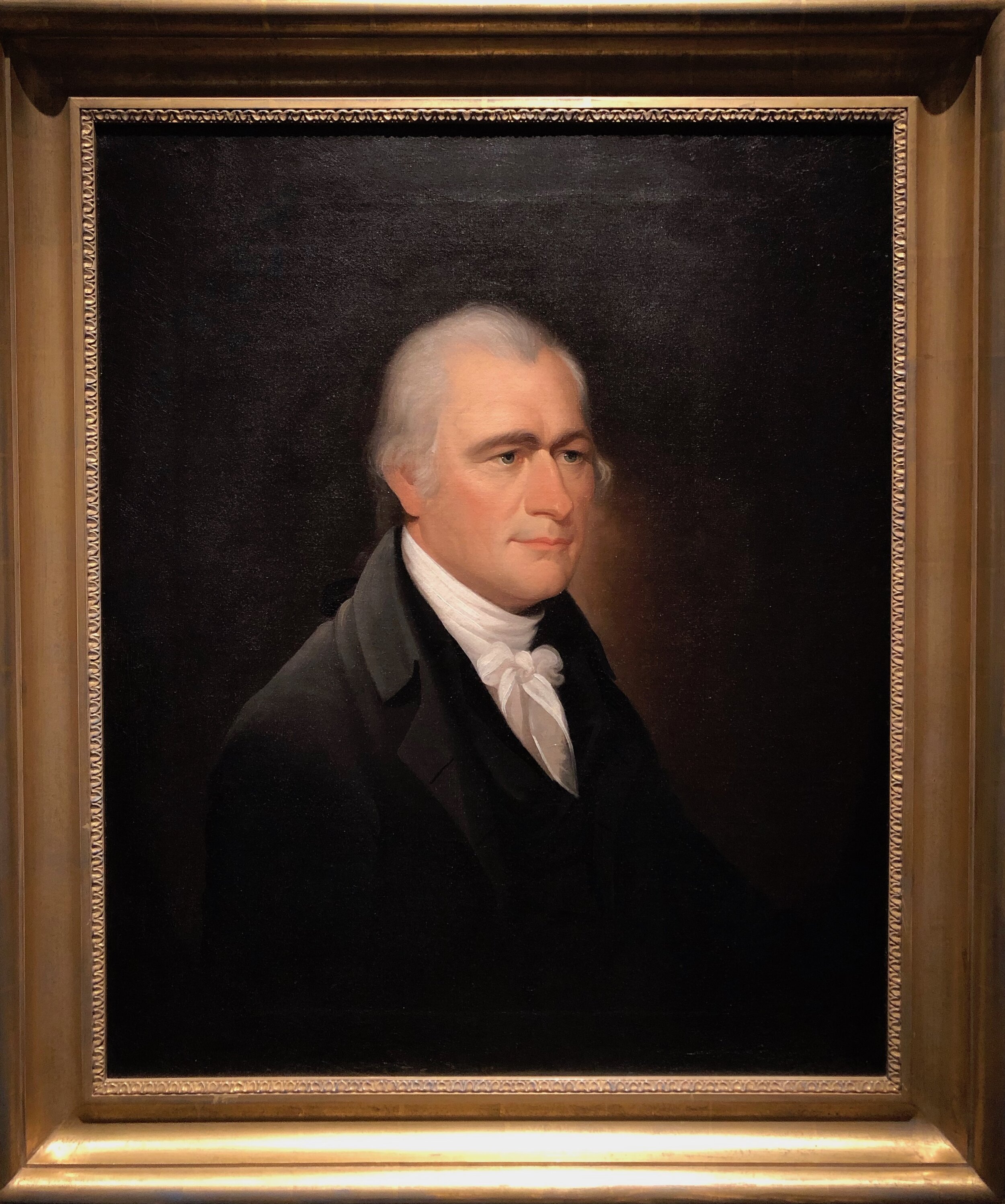

Esther’s journal begins in 1754, after the birth of her daughter Sally and Sarah Prince’s return to Boston, and ends in the autumn of 1757, shortly before the sudden death of Aaron Burr, Sr. From the not-very-flattering portrait of Esther, above, likely painted around the time of her marriage by a now-anonymous artist, it appears that her son’s famously commanding dark eyes, below, also came from his mother.

On February 6, 1756, Esther’s entry in her journal was only a single line: “Fryday morn. Very poorly, not able to write.”

Esther had good reason for feeling “poorly.” Later that day, her son Aaron Burr, Junior was born unexpectedly early. Eighteenth century childbirth was a communal experience, with the mother supported and encouraged through her ordeal by friends and family. When her daughter was born, Esther had had both Sarah Prince and her mother with her. Neither was there for the birth of her second child, and she missed them sorely. It’s also noteworthy that she regretted not having her husband at home for the birth, too. So often fathers in the past are portrayed as being separate and distant during the birth of their children, but it doesn’t sound like that was the case with the Burrs.

Esther didn’t return to her journal until March 26. She’s not joking when she reassures her friend that she is still alive; many 18thc women did perish either from complications or infections while giving birth, or in the days afterwards.

“I am my dear Fidelia yet alive and allowed to tell you so - I have been able to write nothing from the time of my confinement till now…which is 7 weeks since I was delivered of a Son….Had a fine time altho’ it pleased God in infinite wisdome so to order it that Mr Burr was from home….It seemd very gloomy when I found I was actually in Labour to think that I was, as it were, destitute of Earthly friends – No Mother –No Husband and none of my petecular friends…. O my dear God was all these relations more than all to me in the Hour of my distress. Those words in Psalms were my support and comfort thro’ the whole. They that trust in the Lord shall be as Mount Zion that cannot be moved but abideth for ever – and these also, As the Mountains are found about Jerusalem so is the Lord to them that put their trust in him, or words to that purpose – I had a very quick and good time – A very good layingin [post-partum recovery] till abut 3 weeks, then…my little Aaron (for so we call him) was taken very sick so that for some days we did not expect his life–he has never been so well since tho’ he is comfortable at present….”

Her “little Aaron” is often sick throughout the journal, and Esther frequently agonizes over his health and fears that she might lose him. Yet he did live on, and thrive, well into his eighty-first year. Sadly it was Esther herself who did not survive, dying of a fever seven months after her husband in the spring of 1758. She was only twenty-six.

Quotations from The Journal of Esther Edwards Burr 1754-1757, edited by Carol F. Karlsen and Laurie Crumpacker, ©1984, Yale University Press.

Above: Mrs. Aaron Burr (Esther Edwards Burr), artist unknown, c1750-1758, Yale University Art Gallery.

Below: Portrait of Aaron Burr by Gilbert Stuart, c1793, New Jersey Historical Society.

My latest historical novel, The Secret Wife of Aaron Burr, is now available everywhere, in stores and online. Order here.